Description

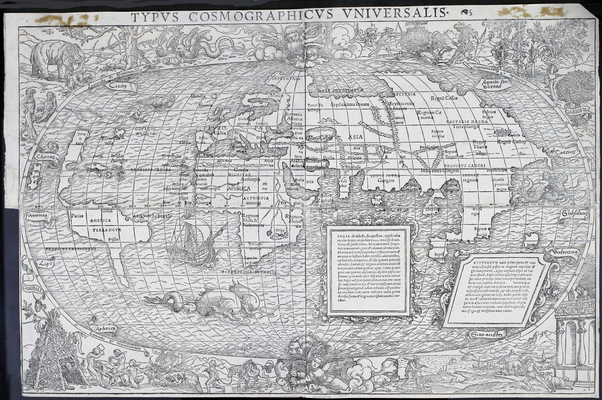

This world map from 1532 is attributed to Sebastian Münster, and the border artwork is attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger. In 1532 both Münster and Holbein were living and working in Basel, in what is now Switzerland. In the mid-16th century the German-speaking city was an active center of printing and publishing known for acceptance of intellectual thought and scholarship in the tumultuous time of the Protestant Reformation.

Sebastian Münster arrived in Basel in the late 1520s to become a professor of Hebrew at the University of Basel. He had been a Franciscan monk and priest prior to embracing the Lutheran Reformation. Münster had extensive theological training, but had also studied mathematics, geography, and astronomy. He published prolifically on both religious and scientific subjects and earned fame as a result of both.

Hans Holbein the Younger was an acclaimed painter who had established himself in Basel beginning in 1515. His career took him throughout Europe, but he flourished in London under the patronage of influential people such as Thomas More and King Henry VIII. He returned to Basel in 1529 at the behest of the Basel City Council, but found prestigious commissions difficult to secure. He began accepting jobs that were available, including orders for title pages and illustrations. Münster likely heard of Holbein’s exceptional talents as a draftsman through their mutual acquaintances in the publishing industry and subsequently engaged him.

In the 16th century scholars often took a two-fold approach to geography. The descriptive approach—grown out of study of the classical texts of Strabo—described the natural environment as well as the way humans interacted with it. The cartographic approach—grown out of a study of the texts of Ptolemy—used mathematics and geometry to explain the shape and size of the features of the physical world.

Münster and Holbein’s 1532 map represents the marriage of these two approaches. Münster’s map depicts the size, shape, and relative proportions of the seas and land masses of the world as they were known to him. Holbein’s artwork comprising the border provides descriptive information in visual form. Look for fanciful depictions of indigenous peoples, including cannibals, hunting scenes, and people with body ornamentation. Exotic spices (cloves, nutmeg, and pepper) decorate the upper right corner. Holbein includes depictions of mountainous terrain; the sea; and domesticated, wild, and mythical animals. Notice Vartomanus at the bottom towards the right. He was an Italian traveler famous in early 16th-century Europe for his account of his adventures in the Middle East and Asia and would have been well known to viewers of the map at the time of publication.

Although neither Münster nor Holbein was famous specifically for his work on this particular map, it neatly demonstrates the Renaissance approach to geography as handled by two masters of their fields.

References:

Leu, Urs B. “The Book and Reading Culture in Basel and Zurich during the Sixteenth Century,” in The Book Triumphant edited by Malcolm Walsby and Graeme Kemp. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2011, 295-319. (LC call number Z8.E9 B65 2011)

McLean, Matthew. “Between Basel and Zurich: Humanist Rivalries and the Works of Sebastian Münster,” in The Book Triumphant edited by Malcolm Walsby and Graeme Kemp. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2011, 270-291. (LC call number Z8.E9 B65 2011)

Pettegree, Andrew. The Book in the Renaissance. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010. (LC call number Z291.3 .P48 2010)

Shirley, Rodney W. “67: Sebastian Münster –Hans Holbein (?)” in The Mapping of the World: Early Printed World Maps 1472-1700. London: The Holland Press, 1983, p. 74-75. (LC call number Ref 3 Lg G3201.S1 S5)

Wilson, Derek. Hans Holbein: Portrait of an Unknown Man. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1996. (LC call number CT 1098.H66 W54 1996)